Michael Giberson

Utility-scale renewable power is sometimes said to suffer from a “chicken and egg” problem when the high quality renewable resources are far from existing customer load or suitable long-distance transmission lines. The asserted problem is that no one would develop the renewable resource unless they have a means to move the power to market, but no one would develop the transmission to move the resource to market until the generation resources were there (or at least under construction).

Development of new, ordinary, non-renewable generation faces the same need to deliver its product to market, but a number of factors make the problem much smaller. In vertically integrated utility systems, the same utility is making transmission and generation plans, and so the chickens and eggs can emerge simultaneously (and no one has to argue whether the chicken or egg must come first).

With merchant generation, the problem is sometimes significant, but generator sites are often selected so as to minimize the amount of transmission building that needs to be done. In addition, interconnection to federally-regulated transmission lines is done via carefully orchestrated processes. While the slow and sometimes awkward interconnection queuing processes present their own problems, the requisite step-by-step movement can help pace generation additions and transmission additions. Development of large merchant generators is also a slow process, allowing transmission additions plenty of time to keep up. On the other hand, if you have the materials in hand then wind power projects can be developed relatively quickly.

The PUC of Texas, with its “Competitive Renewable Energy Zone” (CREZ) process for developing transmission plans in advance of extensive renewable power growth, has been lauded by renewable power advocates for solving the “chicken and egg” problem. As noted here two weeks back, the PUC has recently selected the companies to build transmission lines deemed needed to accommodate existing and forthcoming wind power development. California is developing with a similar effort.

In the broad-scale Eastern Interconnection, which covers most of the U.S. and Canada east of the Rocky Mountain states (excepting the 85 percent of Texas in ERCOT), probably the effort most similar to that pursued by the PUC of Texas is the Joint Coordinated System Planning effort orchestrated by several regional grid operators and related parties. Today, the JCSP folks issued their most recent analysis, estimates of the transmission grid and renewable power investments required under a 5-percent wind power “reference scenario” and a 20-percent wind energy scenario based on the DOE’s Eastern Wind Integration and Transmission Study.

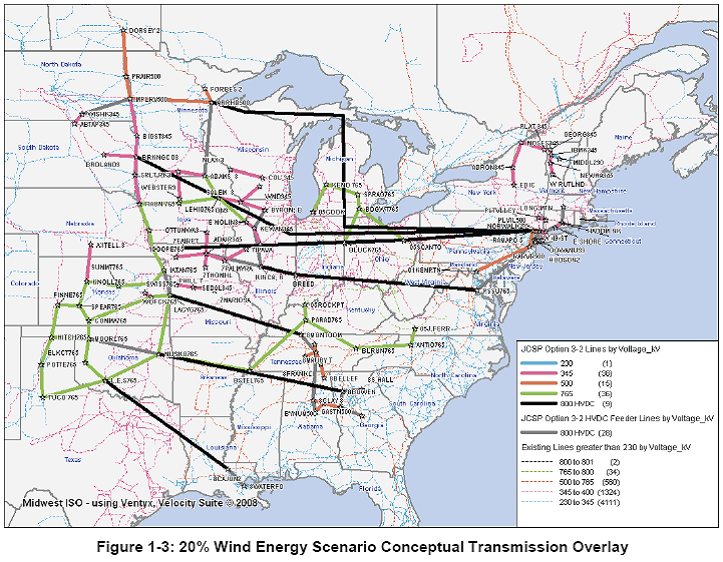

The JCSP 20-percent map looks like this:

The “short answer” is that reaching a 20-percent wind energy scenario is “estimated to require 15,000 miles of new extra-high voltage lines, at an estimated cost of $80 billion, in addition to $1.1 trillion in total generation capital costs by 2024.” The JCSP press release notes, helpfully, “Under both scenarios, the generation capital costs would be borne by developers, while the funding source for the needed transmission is not known at this time.”

Actually, the generation costs are partly borne by taxpayers, via various state and local subsidies, though the bulk of the costs likely fall on project investors in states with restructured wholesale markets. While the funding source of the transmission is “not known at this time,” we know the answer is almost certainly to be transmission rate payers. What is not known is which rate payers will pay how much.

One of the differences between, say, the PUC of Texas and the JCSP effort is that the latter effort is a planning process with no regulatory or ratemaking authority.

- That difference is one reason the funding source of the transmission is “not known.”

- Another reason is that the effort is still in a relatively early stage, much too soon to pin down costs and plan for rates.

- A final reason is that until you start trying to assign cost shares to individual customers, everyone can look at the pretty pictures and smile.

Only later will the sharp knives come out.