Michael Giberson

At Fiscal Times, economist Mark Thoma discusses price gouging and fairness and capitalism. I hoped Thoma had provided the thoughtful defense of price gouging restrictions that John Carney was looking for. Thoma didn’t really–he had a weightier topic in mind and price gouging was just a lever he used to pry open the issue. But he covers enough on price gouging to be worth taking a look at.

With long gas lines and other shortages putting people on edge in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, the usual post-disaster debate over the economics and ethics of price-gouging is underway…

Thoma explains the usual economist’s views: extraordinary prices can motivate extraordinary supply efforts and help allocate goods efficiently, though he omits the demand side rationing benefits usually part of this explanation. Then, allowing the efficiency gains, Thoma wonders why merchants usually don’t raise prices a lot, and why we have laws against efficient responses.

Most of the explanations economists have come up with rely upon the idea of fairness. After a natural disaster, people consider food, water, even goods like gasoline a necessity, and despite attempts by economists to explain that allowing prices to rise is best, they are sensitive to two types of inequities.

First, after a disaster supplies are short, shopping around may be next to impossible, and consumers do not appreciate producers exploiting short-term monopoly power. That’s especially true when they can’t see any obvious way for the higher prices to induce more supply in a reasonable time-frame due to the post-disaster conditions. If consumers feel they are being taken advantage of at a time when they already have enough problems due to the disaster, they might decide to shop elsewhere and this could hurt future sales to the extent that firms will forego price increases.

Second, people do not consider it fair when only the wealthy can get the things they need to ease their troubles. If people have to go without because of an act of god, then everyone should share in the pain. The wealthy should not be able to corner the available supplies of goods and services that are in high demand because of the disaster.

The essay then takes this fairness issue, suggests its importance beyond emergency conditions, and concludes that the endurance of capitalism depends on institutional changes that return us to a less uneven distribution of income. Okay, maybe, but I’ll stick to commenting only on the two price gouging points.

First, it surely seems true that “consumers do not appreciate producers exploiting short-term monopoly power,” the classic citation on this issue being Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler, “Fairness as a constraint on profit-seeking,” American Economic Review, 1986. (KKR) Merchants, understanding this aspect of consumer behavior, often fail to raise prices to market clearing levels and shortages and queues are common results.

Of course the thoughtful economic commentator has a response: Not every consumer reacts in this same way. After all, even in the two Canadian cities that KKR surveyed by telephone for the classic article, not everyone thought it unfair of a hardware store to raise the price of snow shovels the morning after a snowstorm. And social welfare would be improved if people were more willing to allow merchants to adjust prices freely after storms.

Second, “people do not consider it fair when only the wealthy can get the things they need … everyone should share in the pain.” The idea that freely adjusting prices will mean “only the wealthy can get the things they need” is obviously rhetorical excess. The U.S. economy is mostly a place where most prices freely move almost all of the time, and yet non-wealthy people get many of the things they need every day.

Even after natural disasters, an amazing number of non-wealthy people manage to survive. Neither Maryland nor Delaware have price gouging laws, did anyone notice the wealthy snapping up all of the gasoline, canned tuna, and bottled water in those states?

And by the way, it turns out that letting prices adjust helps achieve the result that more people share in the pain. Laws prohibiting price gouging tend to keep the pain localized to just where the natural disaster struck. If the price of gasoline in northern New Jersey had shot up by one or two dollars a gallon for a few days, gasoline trucks and rail cars around the middle Atlantic states and the Northeast would have been diverted to the area. Supplies would have flowed into stations in the affected areas that had power, consumers would have eased up on their hoarding and lines would have dwindled. And, and this is the “share the pain” result that Thoma (and Michael Sandel) find important, gasoline prices around the region would have risen in response to the supply shifts.

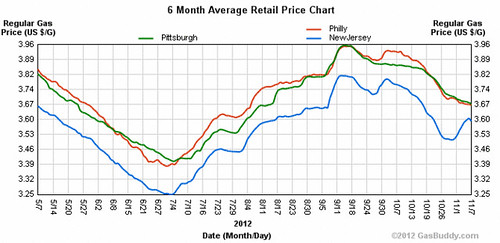

As it happened, gasoline prices in New Jersey rose an average of about 10 cents a gallon statewide after the storm, but that wasn’t enough to motivate extraordinary responses. Notice in this chart that gasoline prices in Philadelphia (in Pennsylvania but just across the river from New Jersey) resemble prices in Pittsburgh (in Pennsylvania but 300 miles to the west), but usually Philadelphia prices share the same market twists and turns as nearby New Jersey. Whatever happened at the end of September had Philly sharing the pain with New Jerseyans. Superstorm Sandy, on the other hand, with anti-price gouging laws prominently on display courtesy of Gov. Chris Christie, saw no sharing of the pain across the river.

The “sharing the pain” issue is examined in Montgomery, Baron, and Weisskopf, “Potential Effects of Proposed Price Gouging Legislation on the Cost and Severity of Gasoline Supply Interruptions,” Journal of Competition Law & Economics, 2007. They estimated that a federal price gouging law would have reduced the flow of goods into areas directly hit by Hurricanes Rita and Katrina and thereby left people there worse off, relatively speaking, and people elsewhere with more stuff.

Yes, maybe people would have their fairness-feelings hurt if prices rose in disaster-struck areas, but just maybe the efficiency gains (i.e., harm more effectively reduced in disaster-struck areas) are worth bruising a few feelings.

[Note: Edited for a few grammatical problems after initial post.-MG]

Pingback: Economist's View: Links for 11-08-2012

This is a nice post from an economic perspective, but it completely misses the mark on the actual gasoline market supply constraints.

– At one point, more than three quarters of fueling stations had no power; regardless of whether they had gasoline in the tanks, they could not sell it to customers.

– Distribution to fueling stations is rather tightly regulated; if prices rose, tanker trucks from Maryland could not have supplied fueling stations in New Jersey.

– Large scale infrastructure was temporarily closed (and some was damaged) due to the storm. NY Harbor was closed, several storage facilities nearby were flooded, and refineries went to reduced operations or were shuttered. This means that rail cars providing extra gasoline to wholesalers would have had no way to unload, just like barges from the Gulf Coast (where a large build in gasoline stocks occurred last week because the Colonial Pipeline was shut) could not have done the same.

– As of October 26, the U.S. East Coast (PADD 1) had 47.9 MMbbl of gasoline in storage, which is something like 20-25 days of supply. While not a high level of stocks, it was certainly plenty to deal with any temporary shortage.

Combined, I think the above makes clear that the “market supply” mechanism was broken between the wholesale and retail level. Wholesalers were generally well supplied (or disruptions were rightly viewed as very temporary), but could not get product to retailers. Maybe the economic arguments still hold, but it’s far from clear that rising prices would have incented more supply to customers.

But the problem was not a shortage of gasoline.

The problem was a shortage of electricity to pump the gas out of the station’s tanks.

So having higher prices attract more supplies would not have solved the problem.

Readers interested in the behavioral economics aspects of price gouging would benefit from reading “The Righteous Mind” by Jonathan Haidt. Haidt focuses extensively on fairness issues as a foundation for morality. Moral foundations impact how individuals interact with each other. Reactions to unfair treatment, such as raising prices during times of crisis, are generally an emotional response unconstrained by rational thought. Rational arguments are poorly suited to changing emotional feelings.

Merchants who expect to stay in business after a natural disaster are at least partially constrained from raising prices as most of their customers are repeat customers who have memories. Reputation is important to merchants. A merchant who is too oportunistic will certainly be punished after the crisis has passed. Temporary monopoly power is temporary and it is not absolute power. Merchants that misjudge the situation and their customers will not survive in business.

The economy and conditions vary over time. Any analysis that considers only a static present is deeply flawed, as is any analysis that expects indiviuals to react rationally, and not emotionally.

@ Mith and Spencer: When talking about extraordinary measures to create supply I am confident that motivated sellers could find temporary power. (You can put a pretty large generator on a truck. You see these at concerts and sporting events all of the time.) They do not have to be reliant on the electrical grid.

While barges and rail cars may be more efficient than tanker trucks, most every filling station takes final delivery from tanker trucks. Tanker trucks could travel from more distant distribution hubs during times of shortages. Higher prices would cover higher costs and allow more product in extraordinay situations. The highly redundant highway systems appears to have been much less impacted by the storm than railroads, ports, and air ports.

It’s good to read a defense of the Irish Potato Famine now and then. 1) It is true that some Irish felt that their starving to death was perfectly fair and reasonable since the market for food cleared properly. 2) It is true that many Irish survived the famine, presumably finding some source of food, and there are lots of Irish alive today to prove it.

As I said, it is good to read this. It reminds us that certain monsters many thought dead are still alive among us.

Pingback: Recomendaciones « intelib

Kaleberg, I’m intrigued by your comment, but I don’t know enough about the Irish potato famine to judge whether my post is actually relevant to that history and whether the facts support your claim that “the market for food cleared properly.”

But more generally, I dispute the idea that promoting policies that encourage assistance to disaster struck regions should be judged monstrous. Let me focus on just one area of disagreement.

In the above post I make at least one very specific empirical claim about how anti-price gouging policy tends to concentrate the effects of the disaster on the directly hit areas, with the result that suffering is increased in the disaster struck area and people elsewhere are less inconvenienced. I illustrate the point with some supportive data (admittedly this isn’t a systematic test) suggesting that the lack of a price response in Philadelphia suggests price caps are impeding a regional response, and I provide a citation to published research which develops the point more completely.

Is it your position that this claim is factually wrong?

Or do you believe it is true, but the suffering that results from the dampened supply effect of price controls is less than the suffering that would result from consumers being presented with higher prices and shorter lines?

One resource on the Irish potato famine: http://irishpotatofamine.net/the-great-irish-famine/