Michael Giberson

One idea advanced by proponents of anti-price gouging laws is that after disaster strikes people should put aside their usual self-interests, join in with the community, and share in the burden of recovery. What these proponents often miss is that normal market adjustments will support a sharing in the burden of recovery, even among those lacking much in the way of charitable impulses, when prices are relatively free to adjust.

Prices go up in the disaster zone, supplies are diverted from elsewhere, prices go up elsewhere, people elsewhere cut back a little in response to higher prices, and there we have it: sharing the pain. Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” is a helping hand to those in need.

But the actions of the “invisible hand” were constrained by the very visible hand of the state. In both New York and New Jersey state officials were prominently threatening to slap businesses with thousands of dollars in fines if prices went up too much. Prices did go up a bit in the disaster struck area, but not enough to prompt extraordinary efforts from elsewhere. New York saw none of that normal, voluntary response to changing supply and demand conditions elsewhere, and post-disaster sacrifices remained concentrated mostly in the hardest hit areas.

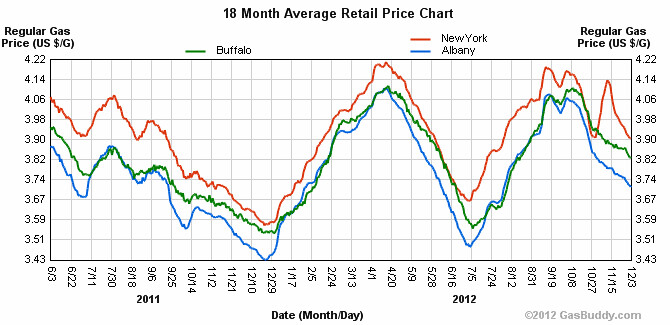

Consider the price chart below, which shows regular gasoline prices in Albany, Buffalo, and New York City, all in New York State, from June of 2011 through the end of November 2012. Typically these prices move up and down together with just a little localized variation. Beginning at the end of October 2012, during Sandy and its aftermath, prices in the New York City moved sharply higher for nearly two weeks. In New York state outside the disaster-struck area, however, gasoline prices barely slowed their descent from late summer highs.

Gasoline lines? Odd-even rationing? Gasoline stations pumped dry? Yes, but only around the power-out, flooded-out, storm-struck area.

Gasoline lines? Odd-even rationing? Gasoline stations pumped dry? Yes, but only around the power-out, flooded-out, storm-struck area.

Elsewhere in the state: business as usual but for the occasional invitation to chip in $10 to the Red Cross.

ROCKETS AND FEATHERS NOTE: Interestingly, Buffalo prices pretty consistently show a slower price descent when prices are falling than either New York City or Albany. I recall that at the end of 2008 a Buffalo-area Congressman was complaining about the same thing. See here and here. The second half of 2008 was a time of fairly consistently falling gasoline prices throughout the U.S., interrupted only by a short lived mid-September price spike due to Hurricane Ike. Gasoline price researchers, start your engines.

Excellent post.

I used to have a nice chart showing diesel prices drifting north in the U.K. following a U.S. hurricane. Same intuition.