Farming has always been an uncertain business. Weather and the price-taking nature of being small relative to large commodity markets lead to feast or famine. The Trump Trade War and today’s palliative farm subsidies to farmers harmed by Trump’s tariffs combine with pre-existing subsidies to amplify that underlying boom and bust cycle, imposing high costs on precisely those people he claims to be helping, including dairy farmers who are more likely now to exit dairy farming.

Even some members of Congress and lobbyists acknowledge that:

“This trade war is cutting the legs out from under farmers and White House’s ‘plan’ is to spend $12 billion on gold crutches,” said Senator Ben Sasse, Republican of Nebraska. “This administration’s tariffs and bailouts aren’t going to make America great again, they’re just going to make it 1929 again.”

One trade group leader said farmers need contracts, not aid, for stability.

“The best relief for the president’s trade war would be ending the trade war,” said Brian Kuehl, the executive director of trade group Farmers for Free Trade, adding, “This proposed action would only be a short-term attempt at masking the long-term damage caused by tariffs.”

Farm groups say their members have already suffered under lower global commodity prices and natural disasters. The prospect of retaliation has further upended global markets for soybeans, meat and other American farm exports, and farmers are warning that tariffs are costing them valuable foreign contracts that took years to win.

The White House has argued that the tariffs are a negotiating strategy that will allow the president to secure better trade deals, and that the pain the tariffs is inflicting is small in comparison to the potential economic gains.

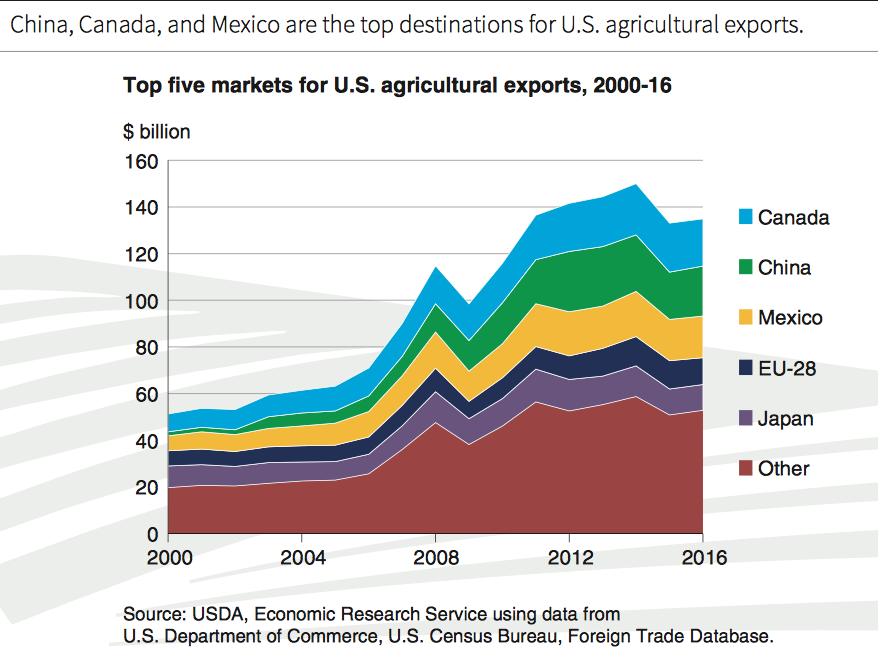

Thus far the Trump Trade War comprises steel, aluminum, and $34 billion of Chinese products. Canada, Mexico, the EU, and China have responded with retaliatory tariffs. China’s imports of US agricultural products accounted for 16% of U.S. agricultural exports (by value) in 2016, and “… the four largest export markets for U.S. agricultural commodities and products—China, Canada, Mexico, and Japan—accounted for 52% of U.S. agriculture export sales (USDA, 2017a).”

Source: Illinois Farm Policy News

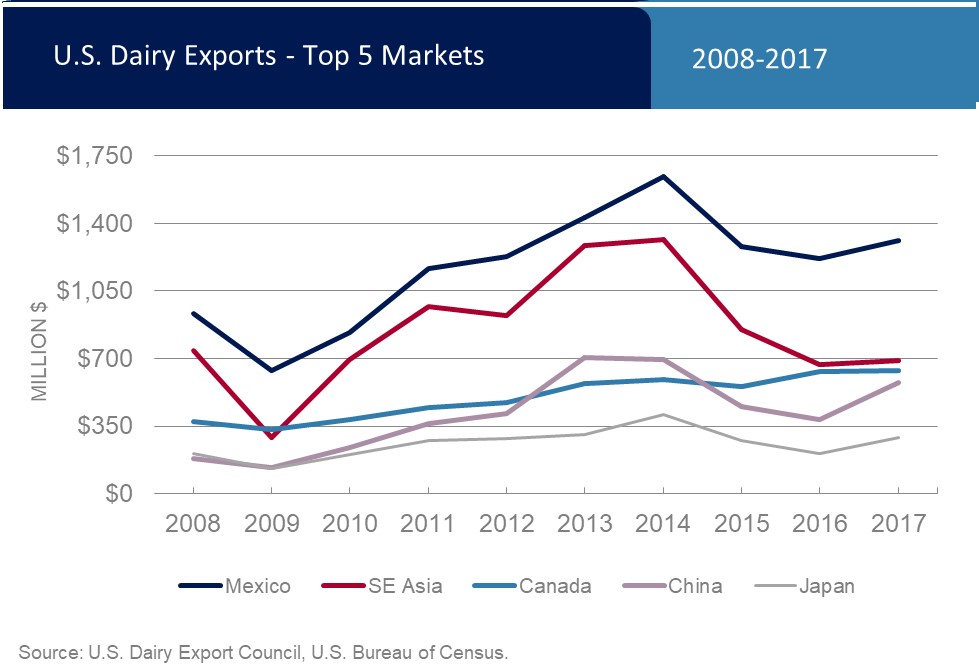

U.S. agricultural industries are likely targets for retaliatory tariffs responding to Trump’s tariffs. For example, 15 percent of dairy produced in the U.S. is exported to world markets, mostly in the form of milk, cream, cheese, whey, or milk solids. China is the third largest export market for U.S. dairy, behind only Mexico and Canada (and surpassed Canada in 2013 and 2014). Mexico imports a lot of cheese from Wisconsin, and one of the first retaliatory tariffs they imposed was on cheese.

Source: U.S. Dairy Export Council

U.S. dairy farmers have been competitive in global markets due in part to increased productivity, mostly in medium to larger sized farms. Higher productivity enables them to accept lower prices. In states like Wisconsin, this productivity increase from farm consolidation and increases in scale has led to a simultaneous reduction in the number of farms and increase in overall milk production.

There were 8,801 dairy herds licensed in Wisconsin as of Jan. 1, 2018. The number of dairies in the state has fallen more than 20 percent in the last five years. But milk production continues to grow every year as many commercial farms expand.

“The growth is really in the medium- to large-size dairy operations,” said Steven Deller, professor of agricultural and applied economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “The growth in those sectors and the increase in productivity of being a bigger operation, the volume of milk is actually not being affected by this.”

Deller said it’s not profitable for dairy farms to operate on a small scale, so the number of commercial farms in the state is likely to continue to decline.

Productivity is a supply-side reason why dairy prices are low, and competition for milk from non-dairy substitutes is a demand-side factor. The problem for farmers is if dairy demand is elastic (like if they face substitutes like almond milk, oat milk, etc.) — in that case lower prices means lower revenue, which is one big reason why farm incomes have always been volatile. The increase in demand coming from export demand in the mid-2010s was a welcome improvement in that profitability potential.

Retaliation to Trump’s tariffs from the top three dairy export markets has had exactly the opposite effect, making U.S. dairy more expensive in export markets:

Mexico buys nearly a quarter of all dairy products exported by the U.S., and the American dairy industry is reeling from $387 million in Mexican tariffs — of between 15 and 25 percent — on cheese.

Hardin, who has been in the industry for decades, says the price that farmers receive for their milk could sink even lower than it is now — putting many farms already in trouble out of business.

“We are looking at a short-term washout of 20 percent of Wisconsin dairy farm milk income on a monthly basis. That’s how dangerous this mess is,” Hardin said.

“However you want to extrapolate the wider economic impact of a $75 million a month drop in Wisconsin dairy farm revenue, it’s painful.” …

Small dairy farms have been disappearing from the rural landscape for decades, but the problem has been compounded by a sharp decline in farm-milk prices that’s now in its third year and has spread across the country.

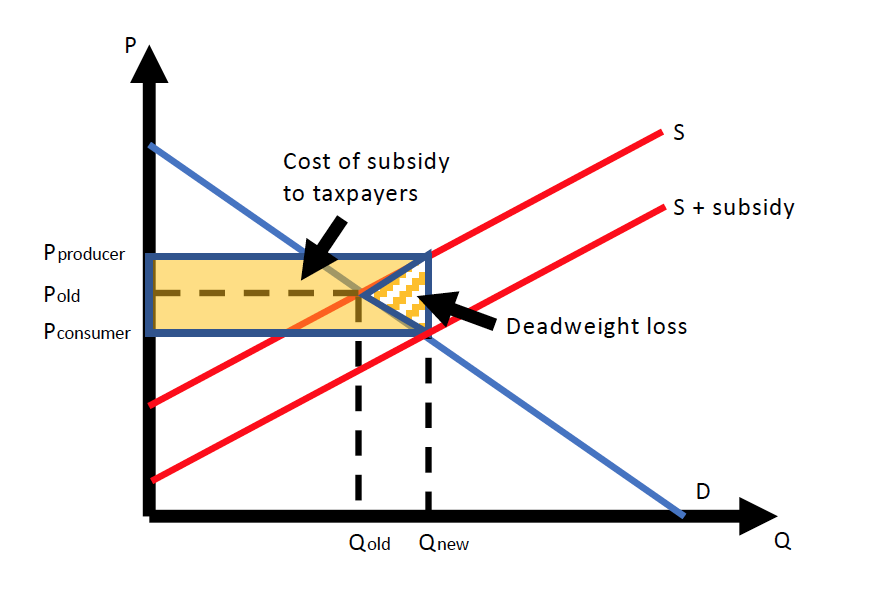

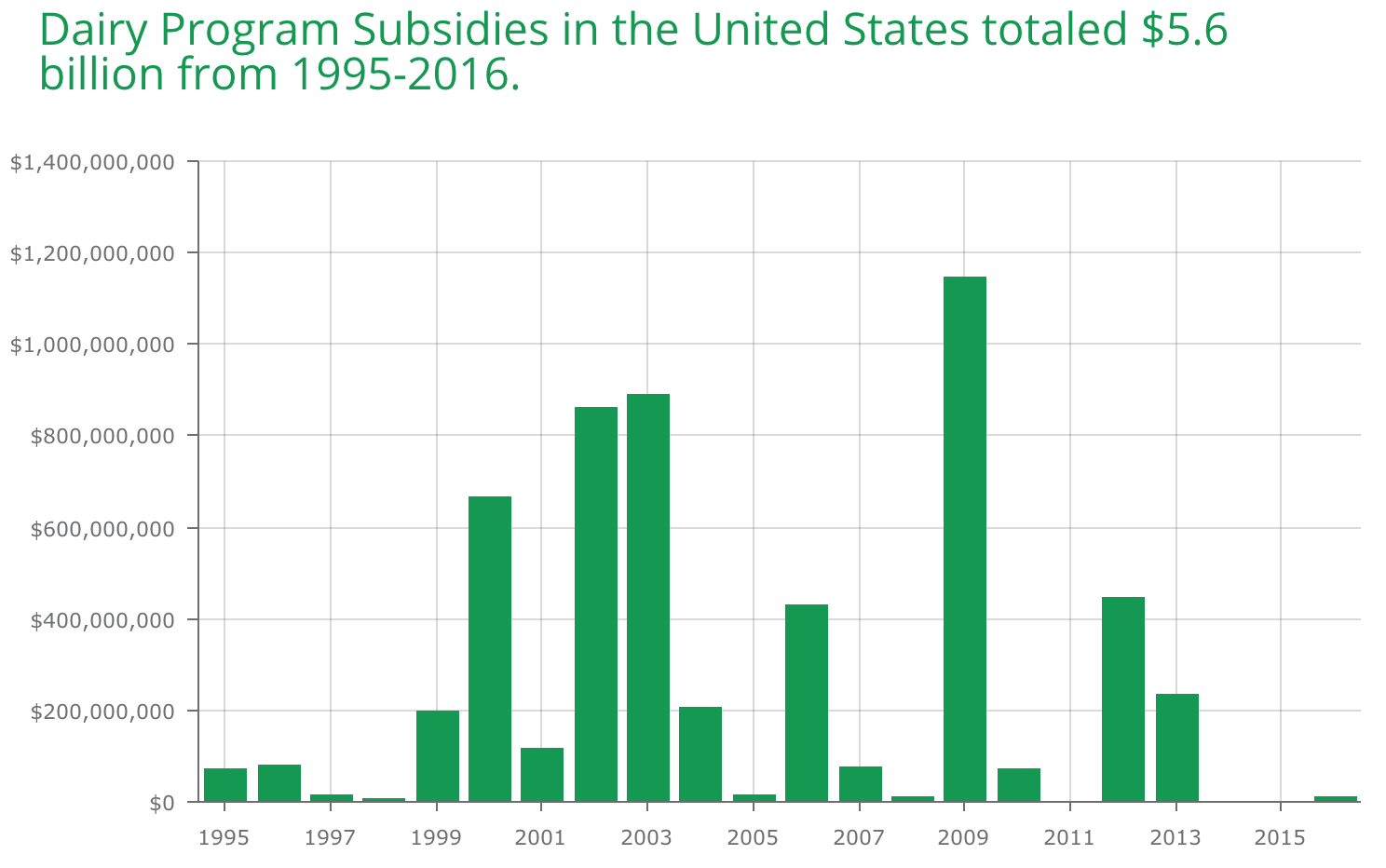

These tariffs aren’t operating in a vacuum — this is an industry that has had farm subsidies and price supports in place for the past century. Subsidies, intended to provide a buffer for farm incomes in the face of volatile commodity prices, contribute to lower prices. Subsidies essentially make farmers willing to accept lower prices because they are receiving a subsidy that creates a wedge between the effective price they receive and the suppressed price that consumers pay. We represent the effect of subsidies in a market as an increase in supply, reflecting the idea that the subsidy makes the producer willing to accept a lower price at all levels of output, impose costs on taxpayers, and create waste (deadweight loss):

The actual policy is a little more nuanced than the model, though, due to some regulatory reform that has targeted the subsidies during low-price periods. The data on dairy subsidy expenditures correlates with times that prices were low (there’s a Pandora’s box there of analysis and interpretation that would be worthwhile to do, but is beyond the scope of this post).

Source: Environmental Working Group, using USDA data

Before the Trump Tariff War U.S. farmers, already experiencing excess supply that led to lower prices in 2017-2018, were exiting the industry due to negative profits. Farms were consolidating, even in the presence of price supports and tax-funded subsidies. Dairy exports were sustaining some farmers that would otherwise have left dairy farming, even with subsidies available. Farmers that are more likely to exit are smaller, as noted above in the news article about Wisconsin. Thus the tariffs catalyze the consolidation already in process in the industry.

Retaliatory tariffs in the Trump Trade War are reducing the export demand that has kept some dairy farmers in the business. Tariffs increase the likelihood that dairy farmers will use subsidies. Today’s announcement of $12 billion in aid to farmers harmed by retaliatory tariffs supplements those existing programs (but apparently are already “on budget”, so not a tax increase). Dairy farmers, especially smaller farmers, and taxpayers will bear the domestic harm. And this is just one narrative of one industry. Add up all of the effects across all of the industries, and how realistic is it to say that all of these “seen and unseen” (pace Bastiat) effects are small in comparison to economic gains?

Pingback: “Any aid package, no matter what dollar amount, is a Band-Aid on an arterial bleed.” – Knowledge Problem